Get Access to 250+ Online Classes

Learn directly from the world’s top investors & entrepreneurs.

Get Started NowIn This Article

Maybe you’ve had it, too—that lightbulb moment. Maybe you’re one of those people who have what you’re sure are brilliant business ideas on a regular basis.

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from Jean Chatzky’s new book “Women with Money: The Judgment-Free Guide to Creating the Joyful, Less Stressed, Purposeful (and, Yes, Rich) Life You Deserve.” In the book, Chatzky uses research from the world's top economists, psychiatrists, behaviorists, and financial planners to help readers explore their relationship with money and how to use it to create the life they want.

JJ Ramberg, the host of the weekly small-business show Your Business on MSNBC, explains the all-too-typical trajectory: “You’re sitting around with your partner or your spouse or your kids and you say, ‘I have this idea!’ Everyone gets excited about it and tells you it’s great and [as a result you’re convinced that] it’s great. And you spend all this time and money on it and you launch it and nobody wants it.”

There are a lot of fantasies we have about starting our own businesses.

One of the most dangerous is the Mrs. Field’s Fantasy. It goes something like this: I make the best/most beautiful/most unusual toffee/succulent gardens/personalized dog paintings anyone has ever seen. If I quit my day job and focused on that, I’d be a gazillionaire.

The problem is the many assumptions within that singular daydream. Is your toffee indeed the best, or is it just the best in your family or your small town?

Will people worldwide want to buy succulent gardens not just tomorrow and next year but for the foreseeable future?

If you did quit your day job, how many dog paintings would you have to create to match your current salary (much less achieve gazillionaire status), and could you do that with just your two hands?

And—this is important—would you continue to enjoy something that you do for pleasure if you had to do it for work?

One of the most common fallacies in starting one’s own business is that because you like doing a thing, you’ll be good at running a business that does that thing.

But running a business is about so much more than making the widget or providing the service.

Say you’re an Etsy seller—not too big a leap as 88 percent of Etsy sellers are women—and your thing is making knitted Minnesota Vikings hats.

Every winter, there’s a surge in orders as people decide one of your creations would make the perfect holiday gift for their tough-to please brother in law. Now imagine that this year the Vikings are the odds-on favorite to win the Super Bowl.

Orders are rising fast. How would you scale to meet that? Would you want to scale to meet that?

Are you ready to hire other knitters or invest in (gasp) knitting machines, to oversee quality control, to deal with the fact that more customers overall may mean more dissatisfied ones?

Do you want to do all this? Or do you just want to create your fabulous hats and make some extra money?

If the Vikings/knitting analogy leaves you dry, there are hundreds of other ways to ask this question.

Do you want to open a restaurant—which requires getting permits, requisitioning supplies, advertising, and marketing—or do you just want to cook?

Do you want to put your fabulous style on display by opening a cutting-edge boutique—which requires ordering, invoicing, staffing—or do you want to find some way to earn money from your fabulous style sense, perhaps by being a stylist or personal shopper?

Is Your Idea A Business or Hobby?

In other words: Is this a business or a hobby (or a side gig, which is somewhere in between)?

If it is a business, is it the sort you can grow or one that just enables you to make a nice living working for yourself?

They are not the same thing.

If you work for yourself and can find a few sustainable clients, you can build a nice, generally stable lifestyle. Building a very large company is something entirely different. So is building a small or midsize company, for that matter.

If you don’t believe me, just look at payroll. As a business owner, payroll has been a huge frustration for me. It’s time consuming if you do it yourself, expensive if you hire out, and even if you do hire out, you have to be constantly watching over your shoulder for mistakes.

There’s a terrifying statistic that one out of three businesses currently does payroll wrong—which means you could be in for costly fines. And payroll is just one tiny little example of all the things that go into the business soup.

By the way, there are no right or wrong answers to this question of scaling versus freelancing, business versus hobby.

The mistake, says Marc Prosser, cofounder of FitSmallBusiness.com, is not understanding the a) difference and b) that you have to choose. In his practice, Prosser sees people who are conflicted.

“They’re either upset that their business isn’t growing or they’re upset about the lifestyle,” he says. “You can have a great lifestyle basically taking on select clients. Or you can try to build a large business. But the two don’t work together.

Is Being a Business Owner in Your DNA?

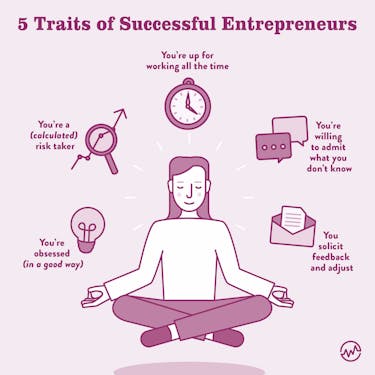

There are certain characteristics that many successful entrepreneurs have.

Trait #1: You’re obsessed (in a good way).

Is it hard for you to get to lunchtime, let alone through the day, without thinking about your idea?

Does building this thing—whatever it is—get your heart beating a little faster? If you’re motivated not by financial gain, not by freedom, but by making sure this enterprise exists in the world, you’re what Susan Oleari, Chicago regional president for BMO Private Bank (who has funded many entrepreneurs over her career), calls a “passionate creator” and have a great shot at both business longevity and business success.

Trait #2: You’re a (calculated) risk taker.

But also a substantial one.

Diving into a business of your own may entail quitting your job (risk), investing your savings (risk), hiring others (risk), and raising capital (risk). Not everybody is suited for that. If you’re unsure, examine the downside.

Before she launched her solar venture, Dana, 50s, from California, took a look at what would happen if the business failed. “I knew that my kids’ college was set and that the worst thing I would have to do was downsize,” she says. “I was perfectly prepared to do that.”

Trait #3: You’re up for working all the time.

If you’re someone who starts work at nine, finishes at six, and always takes the same lunch hour, launching a business (at least the sort you want to grow) may not be for you.

Christin, 30s, from Seattle, says, “What scares me is that it becomes almost an obsession. You have to pour yourself into the company, and I wouldn’t want that to affect my relationship with my husband or take too much time away from my family.”

She’s got a point.

A new business is not unlike a new puppy—what you put in is what you get out. Even those entrepreneurs who are seeking more autonomy—like Dana—often put in long days.

“I probably work sixty hours a week—but before the schedule was not mine,” she says. “I never had much control.”

It’s important to note this start‑up schedule doesn’t have to last forever. Six months after launching the daily newsletter The Skimm, founders Carly Zakin and Danielle Weisberg took back control of their calendars and started scheduling things like exercise, seeing friends and family, and time off e‑mail.

They realized the company wouldn’t be sustainable if they weren’t healthy enough to run it, so they figured out a way to make it happen. More than five years into their successful venture, they still operate this way.

Trait #4: You’re willing to admit what you don’t know.

One of the most important things an entrepreneur does is acknowledge what they don’t know—and be willing to either learn it or surround themselves with people who do, or a combination of the two.

I’ve hired consultants to fill gaps in my full‑time roster, particularly helping me get up to speed with social media strategy because technology is not my strong suit. Which is not to say entrepreneurs shouldn’t have an ego—they should—egos go hand‑in‑hand with confidence.

But confident people also have the ability to say, “I don’t know,” and understand it isn’t a death sentence.

Trait #5: You solicit feedback and adjust.

Kathryn Minshew, founder and CEO of job and career site TheMuse.com, credits this—above all—with her success. (And she is successful—the Muse now employs 120 people and in 2017 raised $20 million in venture funding.)

“I became laser focused on where the criticism and where the kudos were coming from,” she told me on the podcast. “We had thousands of people at the beginning using the site and they would write in and say, ‘I love this. I have never found anything like this product.’ Or, they would be angry at us and they would say, ‘Here are five things you could do to make the site better.’ That, by the way, is great feedback. Because if somebody cares enough to tell you what you could be doing better, especially if it’s things that you want or are planning to do, that’s a sign that you’re onto a need that they’re essentially encouraging you to solve.”

To buy Jean Chatzky’s new book “Women with Money: The Judgment-Free Guide to Creating the Joyful, Less Stressed, Purposeful (and, Yes, Rich) Life You Deserve,” click here. To learn more about Chatzky and hear her discuss the economic power of women and her personal journey to success on the Get WealthFit Podcast, click here.